Guidance for Measuring Benefits

1.Benefits to Investing Stakeholders

Many organisations, both public and private, contribute to the staging of major events, and use them to further their own objectives, such as;

• Rights-owners – increase overall event value and revenue

• City and national governments – increase prosperity of their citizens

• National and international governing bodies – increase sustainable growth

• Tourism and economic development agencies – increase tourism and trade

• Venues – increase current and future footfall and revenue

• Commercial sponsors – increase business sales, brand awareness and engagement

• Community sports or arts organisations – increase current and future participation

• Charities and volunteer organisations – increase involvement and fundraising

• Suppliers – increase business sales and reputation

Whilst each organisation has its own specific objectives, their interests are served collectively by delivering the best possible value from the event in which they are all investing.

Therefore, data measuring the resulting benefits of events needs to be shared in a way which can be used by different organisations, using commonly understood terms. Each section of this guidance includes a glossary of terms.

By sharing how each organisation is measuring success, events can be designed to include activity which delivers value for multiple stakeholders. For example, commercial sponsors funding related community programmes throughout the year and not just for the period of the event.

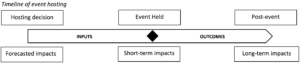

2. Measuring Inputs and Outcomes over time

Major sporting and cultural events can have lasting impacts on communities that host them, and audiences watching them. To fully understand this impact can require detailed longitudinal research over a period extending long after the event has been held.

In practice, this detailed analysis is too costly and time-consuming for most event hosts, rights-owners and other stakeholders. These hosts also need to understand, and communicate, the impact of events long before the full long-term impacts can be assessed. For example, host communities want to understand the value of an event while it is being held, as they do when a decision is being made to host the event, long before it is held.

Therefore, as well as the forecasted or actual outcomes, both in the short and long term, impacts are often expressed in terms of inputs, the projects and resources put in place to deliver outputs at the event and, ultimately, long-term outcomes.

Whilst actual short and long-term outcomes may be unknown until after the event, identifying leading KPIs (key performance indicators) for the inputs can also be useful to monitor progress towards target outcomes and influence decision making in the lead up to an event. Example leading KPIs are included within this guidance.

3. Key Principles for Measurement

Whilst detailed analysis of impacts can be costly the International Association of Event Hosts recommends that, as a minimum, measurement and reporting complies with three guiding principles.

a. Objective-driven – the impacts of events are most effectively expressed in relation to the objectives of the organisations involved in hosting the event. For example, host organisations may support the staging of an event for health benefits to a specific segment of the population, such as inactive residents, or tourism benefits from specific target markets. Therefore, research should be tailored to understand the impacts on relevant audiences and the resulting benefits expressed in the context of these strategic aims.

b. Net additional benefit – benefits should only be reported where they are attributable to an event, and they should also take account of any negative impacts, whether economic, social or environmental. For example, not all expenditure by event spectators in a host economy can be regarded as ‘economic benefit’ when the expenditure from local spectators is not ‘new money’ for the economy. Or the positive social benefits from new infrastructure may come at a cost to some communities relocated or disrupted by the construction.

c. Evidence-based – calculations of impact should be based on robustly gathered input data. For forecasted calculations data should be referenced to demonstrate why it is applicable. Where primary research is used for actual calculations, random sampling or convenience sampling should be representative of target audiences and the quantity of surveys sufficient to be statistically significant. Where forecasts are made to justify the business case for future events, comparable post-event research should also be carried out to review the actual outcomes from the event.

4. Measuring Return on Investment

Hosting events come at a cost to host communities. Assessing net benefit is therefore often used to justify costs and produce a financial ‘return on investment’. However, economists highlight many difficulties in accurately assessing the economic benefit which can be directly compared with financial costs made by the host communities. Therefore, techniques such as Cost Benefit Analysis also exist to allow decision makers to take account of all types of impact, financial and non-financial, over a long period of time.

A key consideration when calculating return on investment or cost benefit analysis, is determining who gains from the benefits, and who is meeting the costs, whether financial or non-financial. Short term economic impacts may mainly benefit businesses in the tourism or construction sectors, whereas the costs may be met by all tax payers across a whole city, region or country.

Irrespective of a forecasted positive return on investment, financial sustainability is a key issue for host organisations and whether they are able to meet costs from the resources available, taking into account the opportunity cost of investing in other projects.

5. Sustainability and Legacy Outcomes

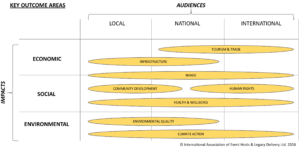

According to the United Nations, sustainable development is the international community’s most urgent priority. For many years national governments and stakeholder organisations have recognised the three interdependent pillars of sustainable development when investing public money: economic development, social development and environmental protection.

As International Standard on Sustainable Event Management, ISO 20121, was developed to help the event industry put sustainability at the heart of decision making when planning and staging events, and good practice is for event organisers to practise sustainable procurement. Many government agencies also have their own legislative frameworks or requirements to meet where public funding is being invested in events.

Therefore, it has become commonplace to express impacts of events in terms of the ‘triple bottom line’ – the three areas of sustainable development, and organisations offer specialism in Economic Impact Assessments, Social Impact Assessments and Environmental Impact Assessments. However, the areas are interdependent, and decisions made in preparation for an event should give consideration to legacy outcomes which have impact across all three areas.

For this guidance the following model demonstrates the most significant areas of outcome from events, mapped against the relevant audiences which influence the scale of these outcomes;

6. Glossary of Terms

Convenience sampling

The practice, where random sampling is not practical, of surveying as large a sample of an event population as possible in order that, it should represent the wider population as reasonably as possible, and the size of the sample minimises any potential biases.

Cost Benefit Analysis

A method of comparing the net benefits of a project with the costs of delivering it, by expressing all types of impact in terms of equivalent monetary value.

Input

For the purposes of events, a planned activity intended to produce an output at the event resulting in short or long-term outcomes.

ISO 20121

The International Standard on Sustainable Event Management, see www.iso20121.org.

Leading KPI (key performance indicator)

A measurable value which indicates progress towards an objective.

Legacy outcomes

Intended and unintended outcomes resulting from the hosting of an event.

Longitudinal research

Research that tracks the attitudes, viewpoints, behaviours etc. of selected individuals over a period of time

Opportunity Cost

Accounting terminology referring to the lost benefit from not making an alternative investment.

Outcome

The resulting consequence of an activity or event.

Primary research

Primary research (also called field research) involves the collection of data that does not already exist. This can be through numerous forms, including questionnaires and telephone interviews.

Random sampling

The practice of surveying a population in which every element in the population has an equal chance of being selected, and in which the resulting sample is representative of the population from which it has been drawn

Return on Investment

A financial calculation of the ratio of net profit gained from an initial investment of resources.

Statistically significant

A mathematical term used to determine whether sampling data is sufficient to represent a whole population.

Sustainable development

Development which meets the needs of the present without compromising the needs of future generations to meet their needs. The United Nations has 17 sustainable development goals, see https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/development-agenda/.